Stop beating up the Rich

September 6, 2012: 5:00 AM ET

Instead of taking them down, shouldn't we figure out how to lift everyone up?

By Nina Easton, senior editor

FORTUNE

-- Alexis de Tocqueville famously chronicled American society's love of

equality -- and its equally passionate pursuit of money. "The love of

wealth," the French historian wrote in the 1840s, "is … at the bottom of

all that the Americans do." America stands out among Western nations

for its grudging, and often fawning, admiration for the wealthy classes

it produces. With the road to riches seemingly wide open, Americans

favor aspiration over resentment, envy over animus.

Except when they don't.

Rebellions against the rich are as much a part of the fabric of

American life as the Horatio Alger myth. One year ago this month, that

rebellion crystallized at lower Manhattan's Zuccotti Park, with the

start of a series of autumnal protests called

Occupy Wall Street.

During summer organizing meetings, anthropologist and former Yale

professor David Graeber had hit on a brilliant marketing formula for the

rebels: "Why not call ourselves the 99%?" he recalled asking fellow

plotters. "If 1% of the population have ended up with all the benefits

of the last 10 years of economic growth, control the wealth, own the

politicians … why not just say we're everybody else?"

In a hotly contested presidential election year, that formula found

easy political resonance. The 99% doesn't just mean the poor or the

unemployed or even the hardhat crowd. It includes the vast middle class

of blue collar and white collar and pink collar -- even the upper middle

class. It's the 99% that defined America's post-World War II economic

might and remains the target of any serious aspirant to the Oval Office.

With head-spinning speed, the 1%-99% divide entered the vocabulary of

journalists, politicians, and voters. More than ever in recent memory,

both a presidential election and

critical policy debates in Washington are being fought through this prism.

Sadly, it is a

confusing and flawed prism,

marred by hyperbole, half-truths, and unnecessary pessimism about what

it means to succeed in America. Yes, in politics, perceptions do matter.

Reports of CEOs making 231 times the average worker's pay, news of fat

Wall Street bonuses often unhinged from performance, and images of

executives flying to Washington on private jets to beg for bailouts feed

fears that the system is hopelessly rigged toward the rich and

powerful. But it's wrong to lump the 1% into a monolithic group of

greedy, tax-avoiding, selfish capitalists. They are a lot different from

what you might think.

MORE: Obama - a president ready for a showdown

Most of the 1.4 million taxpayers who make up the top 1% gained their

wealth through their own efforts rather than by inheritance. This group

consists of a large number of doctors, lawyers, engineers, and

small-time entrepreneurs, many of whom are working hard to create jobs.

To vilify them is the wrong debate. It's a conversation that tends to

cast blame on people who have made it to the top or anywhere near it,

since Obama's tax proposal labels as "wealthy" households making more

than $250,000 a year -- a comfortable income in Indianapolis (where the

median home price is $102,000) but barely enough to afford a studio

apartment in Manhattan, where tax rates easily hit 50%.

It's also a conversation that misses the point. Stirring resentment

and pitting Americans against one another distracts from the harder and

far more important conversation: how to

jump-start the escalator

for 23 million unemployed and underemployed -- and for those whose

incomes were stagnating well before the 2008 recession. Diatribes

against the 1% are provocative and entertaining, but they don't offer a

path to prosperity for those left behind in the global economy. If

Americans really understood who the 1% are, they would be more likely to

stop the name-calling and shift the debate to the dire task at hand --

getting millions back to work.

This isn't the first time an economic downturn has provoked

rebellions against the rich -- and it probably won't be the last. In the

depths of the Great Depression, F.D.R. surprised reporters and members

of Congress with a speech denouncing the "great accumulations of wealth"

and called for a surtax on the rich (which passed). There was political

calculation behind this. It was the summer of 1935, and F.D.R. faced a

threat to his reelection prospects from fiery populist Huey Long. The

Louisiana senator's Save Our Wealth campaign drew some 7 million

followers with a detailed program to cap wealth. Long's assassination

ended that electoral threat; F.D.R. would later joke about his

reputation for eating "grilled millionaire" for breakfast.

Half a century later, with the country pulling out of a relatively

mild recession, presidential candidate Bill Clinton noticed a front-page

New York Times headline shouting the 1980s: a very good time

for the very rich. The article asserted that the "richest 1% of American

families appears to have reaped most of the gains of the last decade

and a half " -- 60% of the wealth to be precise. Within days Clinton was

on the stump denouncing the "unfair gains of the rich" at the expense

of a "forgotten middle class." Eager to protect the image of the

Reagan-era boom times, President George H.W. Bush's administration went

on the offense to undermine the statistics used. But the damage was

done, and while the "1% club" didn't define the election as it does

today, Clinton became (in the words of the

Times) "one of the few presidential candidates since Truman to woo the middle class by pummeling the rich."

Ironically, wealth concentration would accelerate during Clinton's

own boom economy. But the media's characterization of wealth in the

1990s was far more benign than how they portrayed Reagan's greedy

"Gilded Age." That's only one of the many misperceptions that have

enshrouded a debate that has become as much emotional as economic.

It is true that today's wealthy are richer than in the past and their

share of the nation's income has grown. In the late 1970s and early

1980s, the 1% club earned about one-tenth of the nation's income. By

2007 it was 23.5%, the second highest in history after 1929. Cost of

admission to the 1% club varies from year to year, but when measured by

annual income it typically ranges between $300,000 and $400,000.

Net-worth estimates are less reliable and therefore seldom used, but by

one calculation, a household needs $8.4 million to qualify. About half

the 1% qualify in both categories.

MORE: Mitt Romney's 5-point plan for the economy

Are the rich, however, prospering at the expense of the middle class? As economists like to say,

it's not a zero-sum game.

Let's start with the fact that wealth concentration increases in boom

times and, ironically, was ebbing by the time Occupy Wall Street started

organizing. As Steven N. Kaplan, an economist at the University of

Chicago's Booth School of Business, notes, "Inequality in 2009 was

actually lower than at any time during Bill Clinton's second term."

During the booming 1990s inequality shot up -- but the middle class also

gained. In 1998 middle-class families enjoyed the largest one-year gain

in income since 1986, and poverty ticked down.

Over the past four decades the global economy has left many behind, but it has also lifted tens of millions

out of poverty.

In this more nuanced picture, those Americans with valued skills and

advanced educations are reaping the rewards. And here we're talking

about a swath of society well beyond the much-derided 1%: The top 20%

enjoyed strong gains since the late 1970s, and a new Pew Research Center

study found that 60% of Americans say their standard of living is

better than their parents' at the same age.

We hear a lot about a "shrinking" middle class. The Brookings

Institution's Scott Winship, who has done studies on mobility, says the

main reason is that people are moving up -- not down. Indeed,

upper-middle-income ranks have grown.

The Pew Research Center

finds that since the early 1980s middle-class Americans as a percentage

of the population fell from 61% to 51% -- and their median net worth

was flat. But the percentage of upper-income Americans surged from 14%

to 20% of the population.

The actual

number of millionaires

has also grown handily over the past decade. Although the number

dropped during the recession, it is slowly beginning to rebound. A 2011

study by the Deloitte Center for Financial Services found that over the

past decade the number of millionaire households rose from 7.7 million

to 10.5 million and predicts a doubling of American millionaires by

2020.

Another myth about the rich is that they are an exclusive club,

an entrenched plutocracy

that holds on to their fortunes generation after generation. In fact,

the wealth of the top 1% is notoriously volatile and drops precipitously

in recessions and depressions. (By one net-worth estimate, the

millionaire club had shrunk by 85% by the time F.D.R. started grilling

them.) Also, the membership rolls of the 1% club are always in flux.

According to a Federal Reserve study, between 1996 and 2005 some 57% of

the 1% fell out of the club.

Compare any list of today's wealthiest Americans with one of three

decades ago and what's striking is the rise of self-made men and women.

Studies show that most large accumulations of wealth today are earned,

not inherited. A 2008 survey by PNC Wealth Management found that 69% of

those with $500,000 or more in investable assets earned most of their

fortune through work, business ownership, or investments -- compared

with 6% who inherited their money. (Another 25% reported a combination

of earnings and inheritance.)

Regrettably, more wealth than ever in recent history comes not from

building companies but from the art of moving money around. The sloshes

of eye-popping salaries and bonuses on Wall Street unnerve the American

public --

and draw protests.

But even this fact deserves perspective. Finance constitutes only 13%

of the 1% club, according to a study by Williams College's Jon Bakija,

Indiana University's Bradley T. Heim, and the Treasury Department's Adam

Cole. The club also includes nonfinancial executives (30%), doctors

(14%), and lawyers (8%), as well as computer engineers, salespeople,

real estate traders, and, of course, celebrities in sports,

entertainment, and the media. In his book

Richistan, Robert Frank notes the prevalence of "stakeholders," entrepreneurs able to cash in when a company goes public.

MORE: Forget Washington - here's how we'd fix the economy

It's also worth noting that a rarely cited reason behind the phenomenon of the rich getting richer is

the success of women.

Beginning in the 1970s, more women began obtaining advanced degrees,

and making more money -- and then marrying men with similar achievement

levels. According to the Bakija-Heim-Cole study, among households in the

1%, those with a working spouse rose from 25.0% to 38.4% between 1979

and 2005. Type-A personality women tend to marry like-minded men --

social scientists dryly call it "assortative mating" -- and further skew

income at the top.

You may passionately believe that the 1% should pay more than the 40%

of federal income taxes they already contribute. You may think this is

the "fair" way to address a ballooning debt. Fine. But don't kid

yourself that there's enough money there to close the deficit -- and

raising taxes definitely won't cure inequality. You probably think the

average wealthy person pays lower tax rates. That's true for the

super-rich -- reflecting the lower taxes paid on investment income,

which typically makes up the bulk of their earnings. Hearing those

numbers infuriates average taxpayers. That's why the

so-called Buffett rule,

named for Warren Buffett, to impose a minimum 30% rate on

million-dollar incomes gained the White House's support -- and why in

public opinion polls proposals to increase taxes on the rich are hugely

popular.

When you look at the full picture, the average effective tax rate of

the 1% club in 2007 was 29.5%, which, according to the Congressional

Budget Office, is nearly twice that of the middle class. And nearly half

of all Americans -- those with low incomes -- don't pay a federal

income tax, though they do pay the regressive payroll tax and state and

local taxes. In other words, overall our progressive income tax code is

actually … progressive.

When you look beyond all the anti-rich rhetoric, what Americans really want is

more equal opportunity for themselves.

One reason behind the surge in wealth at the top is access to global

markets. Top American lawyers, bankers, consultants, and entrepreneurs

are playing on a wide turf and tapping into fast-growing emerging

markets. Rather than engaging in diatribes against them, we should be

asking how to build access lanes into that global economy for other

Americans. As Harvard economist Lawrence Katz has calculated, even if

Occupy Wall Street's wish came true and all the gains of the top 1%

since 1979 were confiscated and redistributed to the 99%, household

incomes would go up by less than half of what they would if everyone had

a college degree.

During the post-World War II decades, a period of extraordinary

income equality that economists label the Great Compression, Americans

had a relatively common and unifying set of incentives and values that

ultimately served the nation well through the tumult of the '60s and the

Vietnam War. Part of that shared value system was a deep-rooted belief

in social and economic mobility -- a belief powerfully articulated in

the presidency of Barack Obama, the biracial son of a single mom.

Today American upward mobility (especially for men) lags behind Canada's and some European nations'. The

decline in U.S. manufacturing

plays an obvious role. Men with high school diplomas have lost

high-paying jobs to factories in China and India and elsewhere. High

school dropouts, concentrated in inner cities, face even bleaker

prospects of getting ahead.

So the question is, How do we reboot an education system for a

21st-century workforce? In their landmark study on income inequality,

Harvard economists Claudia Goldin and Katz found that America's

educational attainment has slowed, especially compared with competitor

nations, at a time when technological advancement complicates

labor-force needs. Among OECD countries, the U.S. ranks near the bottom

in high school graduation rates and in the middle on college graduation

rates. We used to be at the top. "The slowdown and reversal [in the

U.S.] were so extreme that college graduation rates for young men born

in the mid-1970s are no higher than for those born in the late 1940s,"

the authors write.

Unfortunately,

there's a limit to what policymakers can do about the ravages on a

middle-aged man's job prospects after three decades' worth of

technological advances and global competition. But we can talk about

education:

College degrees,

while not a panacea, not only carry huge salary premiums but also offer

a measure of job protection. Last year's unemployment rate among the

college educated was 4.9%; among those with advanced degrees, it drops

to 2.4%. For those with high school diplomas it was 9.4%, and for those

without, 14%.

We can demand that corporate America invest more in the nation's workforce by

ramping up training programs.

Something is wrong when 3 million job openings are going unfilled, and

companies complain they can't find the right workers with the right

skills. We can ask how American communities can persuade businesses to

locate new offices and factories in their hometowns rather than in

places like China or Poland -- something corporate tax reform can help.

Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter, who runs studies of

U.S. competitiveness, is critical of executive compensation practices

and criticizes companies for a widespread failure to invest in the

American workforce. Nevertheless, he says, "it's not a good idea to

declare that people who are successful are bad. The better question is:

Do we have

a fair system for getting that education and skill? Are people unfairly handicapped? Are we doing enough to open the gateways?"

Mobility, in the form of equal opportunity rather than equal

outcomes, is rooted in the very idea of America -- and that's where the

public conversation over inequality needs to head. "If people never

think of themselves as moving up and out [of their circumstances], does

that then strike at pluralism, democracy, the heart of who we are?" asks

Harvard's Goldin. Our history suggests it's better to open the road to

riches for those Americans than to raid the gold pot at the end of it.

This story is from the September 24, 2012 issue of Fortune

.

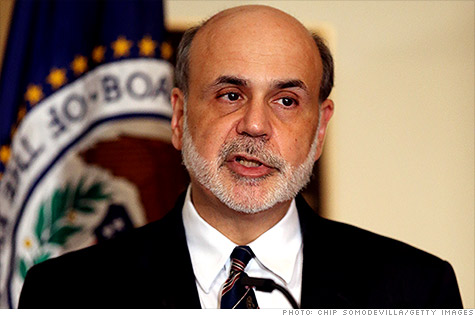

Is the third time the charm? Federal Reserve Chairman Ben

Bernanke certainly hopes so, as the central bank launched QE3 in an

attempt to stimulate the economy.

Is the third time the charm? Federal Reserve Chairman Ben

Bernanke certainly hopes so, as the central bank launched QE3 in an

attempt to stimulate the economy.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- The Federal Reserve's policymaking

committee is meeting for the next two days, and it is widely expected to

announce a third round of quantitative easing, known as QE3.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- The Federal Reserve's policymaking

committee is meeting for the next two days, and it is widely expected to

announce a third round of quantitative easing, known as QE3.